Skinning a Tire—or, a Rite of Passage, Capoeira Angola Style—and, the Opposite of Destruction is Creation

In which I realize that the act of creation is an act of survival and resistance, after recently spending the day working on making a component of the berimbau, Capoeira's signature musical instrument.

A versão em português está aqui

The people who seized power in the US have been more than true to their threat to "flood the zone," sowing chaos, cruelty, and mind-boggling hatred by executive order, hellbent on inflicting destruction and death as effectively as the recent Los Angeles fires nuked entire communities. All of this as 99% of the "opposition" party has flailed about, collaborated, and given up, clinging to the cult of civility, norms, and the mind-boggling belief that "everything is and will go back to normal at the next elections."

Many of us are finding ourselves paddling feverishly against these double currents, trying to stay centered, trying to shield ourselves from cynicism and nihilism, and trying to figure out what it means to "resist" today.

I've been grappling with the fact that I'm currently in Brazil, which means there isn't much I can contribute hands-on in Los Angeles.

However, after attending a Mariame Kaba workshop on activism, the one led by Shannon Downey—author of "Let’s Move the Needle An Activism Handbook for Artists, Crafters, Creatives, and Makers"—I realized that, yes of course, there is something meaningful that I can do.

The Opposite of Destruction is Creation

When fascists are hellbent on destruction, the act of creation is an act of survival. It is a moral imperative. They are trying to kill our spirits (as well as our bodies—eugenics much?), the planet, and everything in between.

To counter the desecraters we must make beautiful things—even if they are just beautiful to us alone—and hold them in our hands, our hearts, and our souls. And we must share them. We must share what we create and why we create them. We must inspire each other. We must keep each other alive.

I felt the soul-affirming gift of this after recently spending the day working on making a component of the berimbau, Capoeira's signature musical instrument, and reflecting on how much I have always loved to make things.

I'd Made Most of a Berimbau Twice Before

I'd made a berimbau twice before. Or to be exact, I'd made most of the many parts of one. But until last week, I'd never extracted the arame (or wire). It had always seemed so impossible and so intimidating.

At the first berimbau-making workshop I attended way back in the earliest days of my time in Capoeira Angola, we worked with biriba—the classic wood used for berimbaus and for which they are named—that had been shipped to Los Angeles from Brazil. My most vivid memory though, is of weaving our caxixis from scratch.

Insights From the Caxixi—a Little Detour

Oh, the caxixi! I yearn to make one again. I can still feel the thrill of seeing that exquisite little percussion instrument begin to emerge from my fingers as they grasped and intertwined the wet tendrils of long grasses to form it. I can still feel my awe at the ingenuity and immemorial wisdom: soaking the dried grasses makes them pliable for weaving, and, added benefit, softens their sharp edges, thereby reducing the risk of painful cuts.

And those grasses, of course they transported me back to my beloved veld, the grasslands of Mpumalanga which—when I walked them as a child, my roving eye on alert for mambas, puff adders, and other dangers—was known as the Eastern Transvaal under the apartheid regime in South Africa. (btw, I wasn't alone on those walks. There was always at least one adult with anti-venom and a rifle just in case.)

Suddenly, all these decades later, the dots connect as I full-body flinch remembering my racist, misogynist relatives who spewed, like a relentless magma flow, their hatred and contempt for basket-weaving, of all things.

The extreme disdain they had for this most creative and useful and enduring art form (whose origins can be traced to the Pre-Pottery Neolithic), tastes and smells just like the anti-humanities (and anti-Humanity) toxic masculinity of the fascists currently on a rampage in the United States and elsewhere. This all strikes me as yet another example of how racism, colonialism, domination ideology, extraction-madness, industrialization, tech-idolatry, patriarchy, etc. have well and truly messed up the world we live in.

And, that is precisely why I am writing about making a berimbau. Which is really about Capoeira Angola, whose ancient, grounding wisdom has so much to teach us.

My Second Berimbau

Last July, here in São Paulo, I made a berimbau again. This time, when I selected the verga from the collection of conduru and biriba branches that Mestre Budião had harvested on the island of Itaparica, it was with so much more confidence than I'd had back then in Los Angeles. I just knew which branch of biriba was calling my name. Something in me had matured. I was Open to the Messages.

This time I learned to strip the bark from the branch.

This time I finessed the foot, sanding and polishing it to the standard I developed in my ceramics practice per the exhortation of Biliana Popova, my most important ceramics professor, to make the underside of every piece as smooth as a baby's bottom.

And the arame? Well, a few months ago, cutting into the tire? That was still much too scary.

Tire and Wire

I am a grown-ass woman. I came all the way out to Brazil knowing just one person and some rudimentary, self-taught Portuguese. I've made it through all sorts of bonkers life stuff including multiple cancers. And yet, all these years, at the idea of tackling the tire I'd always felt like a little girl. Not that little girl who walked the veld. But the unprotected little girl bullied by members of her family. Is it that when I considered the idea of the tire, something in me expected to screw up, and to be berated, humiliated, or worse? Did I subconsciously conflate the big, dirty, cumbersome tire with the whole car it had once belonged to and expect it to slam into me and run me over?

Last week though, when the opportunity presented itself, I immediately responded with a full-hearted YES! No trepidation, no fear, just curiosity and enthusiasm. I was ready. And that was before learning that I’d be working with a motorcycle tire, so small and light as to evoke a toy.

Something in me had changed further. One the one hand it's the fury—my fury at the violation of our shared humanity by these broligarchs—it's the Moral Injury. And on the other, it's the clear messages that I'd been continuing to open myself to receiving. From our Capoeira Mãe (Mother Capoeira), the Universe, and perhaps even, dare I say it, the Orixás. That I was brought here to Brazil for this. And it's time for me to share more actively about it.

Capoeira Nurtures Survival and Cultivates Humanity—So Must We.

As it was taught to me, and as I understand it, Capoeira is resistance. It embodies Resistance to Oppression. As I wrote about it before:

"Capoeira Angola is interdisciplinary, holistic, multifaceted, complex. It’s a dance-fight-game-but-not-really-a-fight-but-could-be-a-fight. It’s an art-social-intellectual-wisdom-life-spiritual-community-educational-political-healing practice. It’s ritual. It nurtures survival. It’s play. It facilitates liberation. It’s sustenance. It cultivates humanity."

And one way to nurture survival and cultivate humanity is to make things, to make the things we need. You can always go and buy a berimbau. But making one? That takes some doing.

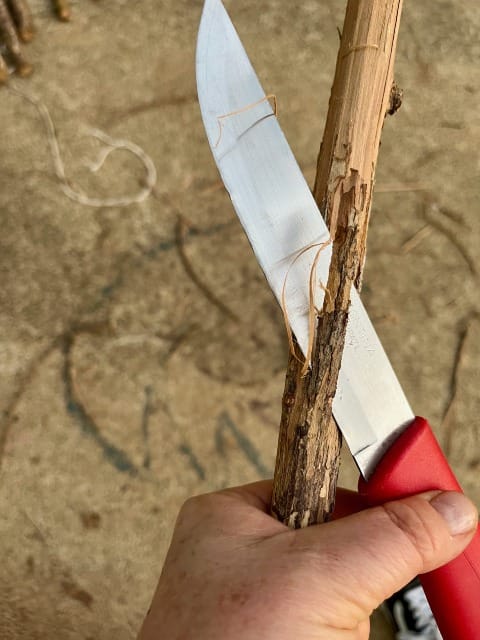

You can always go and buy some piano wire if you need another arame. But extracting the arame from the tire? That requires some serious labor: First you cut into the tire and dig in with the blade until you feel it connect to the steel wire. And then, as you'll see in the video below, you saw away at it while both maintaining that connection (easier said than done, and I did a less than perfect job but kept at it, determined to prevail), and pulling hard on the rubber as you liberate it.

Video of me cutting into the rubber on a motorcycle tire to extract the wire for the arame. Filmed by Mestre Budião, February 2025

Then comes the fun part—standing on the tire and pulling the wire all the way out (see the video below)!

Video of me pulling the wire from the tire. Filmed by Mestre Budião, February 2025

I'm looking forward to soon completing the work on this arame. I'll clean it of all rubber remnants, cut it to the appropriate length for the berimbau, sand the wire to polish it further, create loops at each end... This motorcycle tire has yielded enough for at least 8 individual arames. There'll be some for me and some to share, so we can continue to make beautiful Capoeira music in community.

In Conclusion

Reflecting on my afternoon with the tire, I am overcome by a deep and quiet sense of pride and accomplishment. It feels like I’ve been through a significant rite of passage: I am now an Angoleira who can wield knife to tire.

Every time we make something, we exercise our competence. But that’s not enough. Now more than ever, I know that we have to remember to pause and acknowledge each accomplishment. It’s how we build confidence, it’s how we fuel our much-needed courage, it’s how we know we matter. And if we could just channel the little kid who jumps up and down exclaiming “I did that!” we’d get a dose of life-affirming glee.

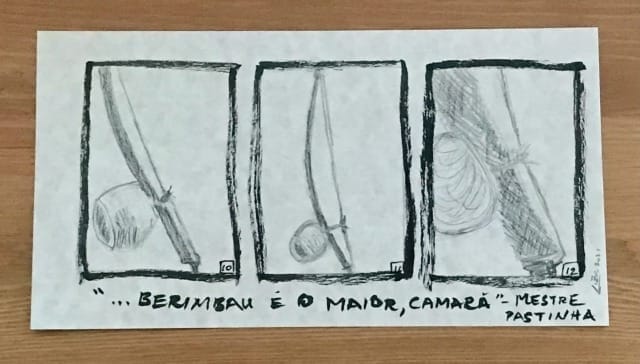

Writing this post also reminded me how much I've always loved experimenting and making things—I realized I had sketches I could use to illustrate it, as well as prior writings to share, as below.

In conclusion, the good news is that when countering doom and destruction, there's always more to learn and more to be done. With that, this excerpt from a story I wrote during the SmokeLong Quarterly's 2022 summer writing workshop comes to mind:

“Make things with love and with care. Touch and honor the earth. Keep going. That is the truth.”

May we stay true to our hearts and our souls. May we stay true to our values. May we lift and hold each other up in connection and community. May we make things with love and with care. May we touch and honor the earth. May we keep going.

Axé